Profile: Peter VandenBerge

For the past 35 years Peter VandenBerge has been creating outsized ceramic busts whose hand-worked features are as mesmerizing as they are confounding. The mystery of these elongated, primitive faces resides primarily in the slit eyes and oblong noses; but their whimsical ornamentation and outlandish headgear – a distinct brand of ‘60s-era, Duchamp-influenced absurdism – seems to mock their otherwise inward-looking demeanor. This month, seven of his busts will be on display at the Solomon Dubnick Gallery, along with works by his daughter, Camille, 40. An equal number of pieces from the elder VandenBerge, now 74, are also on display in a group show, “Three Friends: Fifty Years”, at the CSUS Annex Gallery through Nov. 13.

One of the sculptor’s most recognizable themes is topping his figures, which often resemble South Sea Islanders, with caricaturized automobiles that look they were pulled from R. Crumb’s Zap Comix. The obvious metaphor, of “cars on the brain”, is as blatant as those telegraphed by similarly styled heads that in many instances look like they could have been imported from Balinese temples. Those, too, VandenBerge crowns with airplanes, houses, birds, cows, baseballs and other everyday objects – all without allowing the faces to betray the slightest hint of irony, self-consciousness or pastiche. (VandenBerge says he got the idea for topping his sculptures from photographs he’d seen of Madagascar where tribes place various forms atop graves to depict the lives of the deceased.)

In the mid-1970s, when his career took off, East Coast critics who were unfamiliar (or else hostile) to the comic spirit of the West Coast Funk tradition from which VandenBerg’s ceramics spring, wondered aloud if his work was confused. To that the sculptor asks, “Can’t one be serious and funny?” The obvious answer, given VandenBerge’s stature in the front rank of ceramic sculpture, is “yes”. His work has been exhibited at SF MOMA, the Smithsonian Institute, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Louvre, and the Shigioki Museum in Japan. None of which does anything to silence the charge that his busts are the visual equivalent of “Have a nice day”.

In some part they may be. Still, you’d be wrong to categorize VandenBerge’s aesthetic as mere folly. His most obvious influences, apart from a childhood spent Holland and in Indonesia, are Modigliani and Giacometti, two artists who exposed the human soul by emaciating figures to such an extreme that the only thing left was bare essence. VandenBerge achieves the same effect through opposite means. Where Giacometti’s sculptures are monumental exercise in subtraction, VandenBerge’s heads are about the piling on of material. He rolls out clay in long cylindrical ropes, and then builds his figures by coiling the strands vertically to the desired height. The overall shape and specific features are molded by hand, then daubed with earth-toned pigments that, when fired, bear little resemblance to the shiny glazes so often associated with ceramic schlock. Alternately, in an act of self-appropriation (or perhaps simple recycling), VandenBerge has lately been molding clay around existing busts and then peeling it off in slabs to create new heads with completely hollow interiors that bear little or no resemblance to the originals. His recent homage to his native country, the Netherlands, Amsterdame, with its window-shaped eyes, is a good example.

Regardless of how they come into being, VandenBerge’s heads always have individual topographies. With chisels, forks, knives and other abrasive tools, he works the surface of his objects in an almost painterly fashion – so much so that one writer actually termed the work “painting in three dimensions.” What’s less apparent to the casual view is the degree to which this work represents a profound transformation of personal tragedy.

Living as a Dutch citizen with his family in Indonesia, where his father worked as a geologist for Shell Oil, VandenBerge, at age seven, traveled to remote regions of the Javanese and Sumatran jungles. While his father scratched the earth for signs of oil, young Peter observed exotic flora and fauna: monkeys, crocodiles, elephants and the like, and people whose countenances were, like those in his sculptures, decidedly non-European.

It was wild stuff for a kid born in The Hague. In a home situated on a mountaintop outside Jakarta, Peter – despite his family’s privileged position – lived pretty much like a native. “I was obsessed with making things out of clay,” he recalls in sipping a cappuccino in a coffeehouse a few blocks from his East Sacramento home. “I was like Pigpen,” the Peanuts character. “My mother and father were always telling me to get out of the mud.” VandenBerge also remembers being entranced by the leather figures Javanese shadow puppeteers used to illustrate epic narratives that held pre-TV-era children transfixed.

In 1942, the same year VandenBerge’s dream began, it ended abruptly. When the Japanese invaded Indonesia (also in search of oil) and herded the population into POW camps, the VandenBergs’ life became a living hell. “The whole goddamn thing was a nightmare,” he recalls. “There was not enough food, there were no sanitary conditions, and people were bashed around; they were dying like flies.” When the war ended in 1945 and Shell evacuated the family to Australia in the wake of Sukarno’s revolt against the Dutch, “we were just about dead; we looked like those guys in Somalia.”

After a year in Australia and a few years in post-war Holland, VandenBerg’s father moved to California, and Peter, then 19, followed. Twice over the next several years he returned to Europe where he visited Giacometti and Joan Miró. The impressions made on him by both artists were long-lasting, and as a result, he’s continued, throughout his career, to employ the color palettes and gestures of artists who he admires. Two examples in the Solomon Dubnick show are Bonnard at Le Cannef and Jonah Under Surveillance, where the deep grooves of the character’s beard bring to mind Van Gough’s brushstrokes. About a decade ago, I also recall VandenBerge executing a bust that incorporated a credible rendition of De Kooning’s slashing brushstrokes.

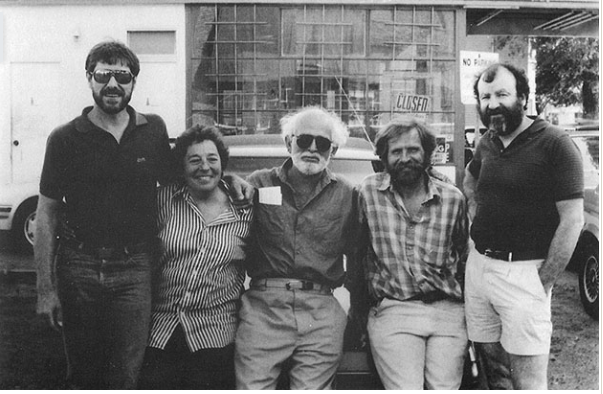

Backtrack to UC Davis, 1962. There, in the company of virtually every innovator in the then-emerging California Funk movement (Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest and William Wiley), VandenBerge began working, as Arneson’s first graduate student assistant, toward an MA degree. Arneson, of course, was the ringleader of that revolution, and would later gain notoriety for his scathing anti-war

Houghstatements and his bust of assassinated San Francisco

Mayor George Moscone. Arneson’s mission was to take ceramics out of the lowly realm of crafts and inject it into the world of fine art.

It was a period of wild experimentation, of finding out what could and could not be done with clay, and of pushing ideas and techniques beyond previously accepted limits. Fueled by political tensions, loosened sexual mores, ‘60s style surrealism and a distaste for the cold conceptual art then sweeping New York (and a good bit of the Bay Area, too), Northern California Funk artists succeeded briefly in tilting the axis of cultural authority to the West Coast.

Arneson was building clay telephones based on human genitalia; Wayne Thiebaud (who opens a show next month at the CSUS Library Gallery) was deep into pop, making pictures of candies, cakes and pies; while VandenBerge, for his part, was casting clay vegetables with crazy anthropomorphic features. But it wasn’t until 1975 that he made the connection with his past that enabled him to forge a signature style. “The linkage between where I came from – the temples where I was growing up and the Indonesian puppet theater – that,” he says emphatically, “was my link.”

The result – clay heads that bear a strong resemblance to the much mythologized East Island figures – have been VandenBerge’s trademark ever since. Despite the fact that WWII influenced him deeply, these ethereal (but wry) figures reveal none of the anger and outrage that his immediate contemporaries, Arneson and Wiley, were expressing about America’s involvement in Vietnam. VanderBerge’s highly symbolic figures have always been about primitive man’s collision with modernity, and by extension, his own loss of innocence in the face of forces far beyond his control.

If they make you smile, well, VandenBerge doesn’t mind. His main concern in the studio, he says, is the simple “pulling and pushing and punching of clay – the physical act of working it to see what I’m going to come up with next.”

-DAVID M. ROTH